The Age of Energy Scarcity

A Brave New World

A Discussion with Jeff Rubin, author of Why Your World Is About To Get A Whole Lot Smaller

By Jeff Fritz

Design by Andrea Barros

(First published in the Arbitrage Magazine Issue 3)

There is an assumption many on this Earth share, one that says the world revolves around money. It doesn’t. It revolves around oil. Cheap oil. And without it, the gears that run this current, globalized economy will come screeching to a halt.

Over the last few decades, ever since M. King Hubbert made his seminal 1956 speech to a gathering of the Petroleum Association of America, in San Antonio, there have been some who have warned about a period in the future when the demand for petroleum will outpace supply, i.e. when we need more oil than we can produce. Unfortunately, today’s experts predict that future is soon upon us.

And that future has a name: Peak Oil.

While our politicians shy away from discussing it and much of the mainstream media still barely cover it, Peak Oil remains a reality. For the facts are: oil is a finite resource (i.e. it won’t last forever). The number of new oil field discoveries have consistently gone down every year for the past three decades. And many geological reports are beginning to indicate a steady decline in the absolute quantity of petroleum being produced from the world’s largest oil producing states.

Altogether, many geologists and former oil industry employees are predicting that within the next decade, production of oil will peak and oil shortages will begin to become commonplace. This will have serious social and economic repercussions and one that will need legislative and technologically innovative measures to overcome it.

Sizing Up the Issue

To get a sense of how important cheap oil is, how ingrained it is in every aspect of our society, let’s take a look back to the waning months of 2008. While much of the world was rapt up in the drama of whether Obama was going to win the primary, much of the world was also rapt with worry over the price of gas (by July, 2008, it sat at $147 a barrel). In some places, it got to the point where talking about oil became like talking about the weather. What you did, how you lived, more and more began to depend on how high up the price of gas rose.

And with good reason.

For those living in suburbia, some had to make the choice of going to work or staying home, since the cost of commuting became unaffordable. This triple-digit rise in gas prices led to less money in people’s pockets, meaning less money to spend on everyday goods—thereby hurting businesses, causing layoffs and ultimately bankruptcies. We saw this drawn out most in the crippling of the auto industry and similarly, to the airlines.

This dip in consumer spending wouldn’t have been so bad were it not for the rabid inflation that accompanied this spike in oil prices. In the US, the headline consumer price inflation rate rose from around two per cent to almost six. But why would this be so? How is the price of oil tied into the price of food and other everyday goods?

The answer is that modern food production is based upon using petroleum based pesticides and fertilizers; thus, rising fuel costs mean rising food prices. The answer is that modern globalization is largely based upon shipping goods from countries where the cost of labour is low to countries where the consumers are rich; thus, when oil prices rise, so too the shipping costs involved and so too will the prices of goods reflect that.

Behind the Obvious

But over the past year, there has been somebody who has taken these links one step farther. Jeff Rubin, the former Chief Economist for the CIBC and recent author of the bestselling book, Why Your World Is About To Get A Whole Lot Smaller, in a phone interview with the Arbitrage, made sure to point out that “we have mistaken this recession as a financial market crisis, when in fact it was an energy shock.”

His assertion is that as oil prices rose in the latter months of 2008, pushing inflation to ever-greater heights, it forced the US Federal Reserve Board to increase interest rates to stem that rise. Unfortunately, that meant homeowners with high or fluctuating (subprime) mortgage rates saw their monthly mortgage payments shoot through the roof and, for those who couldn’t afford to pay, that meant they were out of a home. Repeat this effect for a few million homeowners across America and the result was the implosion of the financial markets, the threat of a second Depression and the subsequent bailout of banks and other financial institutions across the world.

The Hook

This was but one of the insights Rubin shared during our conversation. And it is one that he also outlines more thoroughly in his bestselling book, of which much of the introductory content above was drawn from.

But what is it about the issue of Peak Oil, or energy scarcity that attracted his attention so. Why this above all other issues in this world, such as global poverty or climate change?

As Rubin explains, “I guess it happened 10 years ago. I read this obscure book called, The Coming Oil Crisis, by Dr. Colin Cambell, who as a retired geologist that worked for a number of major oil companies in his lifetime. Basically, he talked [oil] depletion.

“I thought he brought forth a pretty compelling case. That net, we were running faster to stand still (i.e. using more oil to maintain our current standard of living).

“That’s what sort of got me going. I’m not a geologist, but by applying their research to my field [economics], it did get me thinking of some of the economic implications of Peak Oil or depletion.

Rubin explained further that, “from the economist’s perspective, the supply of oil is really a function of price. For example; when world prices of oil are $20 a barrel, the 165 billion barrels of oil trapped in the Tar Sands of Alberta isn’t really an economic resource, since converting tar sands into oil would cost about four times as much as what the market is offering. It may exist geologically, but for all intents and purposes, it’s not a economically viable resource.

“But in a world of $80 a barrel, all of a sudden you’re producing 1 million barrels [of oil] a day out of there. And in a world of $200, we could see (that rise to) 3-4 million barrels … .

“But the paradox of higher energy prices, is that we can’t afford to consume the new supply that it brings. The same [oil] prices that will lift 4 million barrels a day of production out of the Canadian tar sands for example, will translate into retail gasoline prices that will take millions of drivers of the road.”

“(On the whole, that’s what) I’m more interested in: what the economic response to this will be, how will a rational price based economy respond to these kinds of energy prices when this is the one commodity that the whole global economy runs on.”

The Line Is Drawn

Unfortunately, this economic response might be something the world will face sooner rather than later. For as of last December, the IEA placed a fairly definitive date for peak oil at 2020, that is if no new discoveries are made and if oil demand grows on a business-as-usual basis. When asked if this was a sign of some kind, Rubin was quick to reply.

“If you’re familiar with what’s happened with the IEA, you’ll realize that every year the IEA has dramatically reduced its estimates of future world oil supply.”

Rubin then made reference to a Guardian of London exposé (published on Nov. 9th, 2009) that revealed how an IEA official admitted that “many inside the organisation believe that maintaining oil supplies at even 90m to 95m barrels a day (to meet future demand) would be impossible but there are fears that panic could spread on the financial markets if the figures were brought down further. And the Americans fear the end of oil supremacy because it would threaten their power over access to oil resources.”

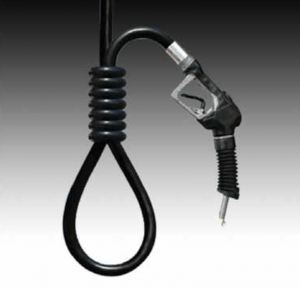

Out of this admission, it would seem that the world’s ability to maintain low oil prices will soon weaken. A conclusion Rubin shares, as he sees triple-digit oil prices returning sooner than later. His concern however, is the next time oil prices surge into triple-digit territory, whether “the global economy (will) be in any better position to withstand those pressures [the effects of high oil prices] than it was in 2008.”

Rubin explained that “(we’ve already) run up record deficits, particularly in the US, billions and billions have been used to prop up financial institutions. And now that we have those record deficits, what’s going to happen is that the next time triple-digit oil prices hit us, not only will there be no more room to stimulate the economy with further deficits, but we’ll start to have to pay back our current deficits.

“So whereas last time triple-digit oil prices hit, we stepped on the fiscal accelerator by ramping up government spending, (all to) bail out the home owners, bail out the auto companies and bail out the investment banks in New York; this time we’re going have to be raising taxes and cutting back spending and that’s going to be a lot more challenging.”

The Way Forward

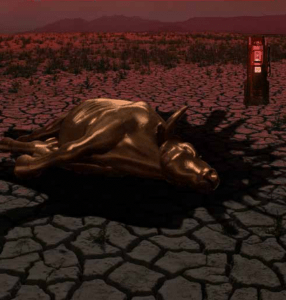

From everything Rubin thus far shared, you might be able to see the overall direction he and many other Peak Oil theorists are pointing to: that Peak Oil may actually be Peak GDP. This essentially means that the economy can only grow when oil is plentiful and when it isn’t, our economy, our standard of living we’ve grown accustomed to, will be threatened.

But does it have to be this way? Rubin doesn’t believe so. And that’s the whole message of his book. “ … We can’t stop oil prices from getting back to triple digit levels and, indeed, we won’t be able to stop oil prices from going even above the $147 a barrel … . But what I think we can do, is make sure that when that does happen, it doesn’t necessarily have to have the same kind of devastating impact on our economy and on our lives than it has in our past.

“The key to that is by changing not the nature of what we burn [oil], but changing the nature of the economy. So the single largest thing we can do to immunize the economy from triple digit oil prices is to go from the model of a global economy to a model of a local economy, because a global economy is an extremely energy—and in particular oil intensive—way of doing business.”

So when asked what can be done, Rubin first outlined how he feels the government should both place a price on carbon domestically to encourage local producers to find ways to cut their emissions, while also placing a carbon tariff on those increasingly large carbon emitters, such as China and India.

“One thing is very clear, no matter where you stand on the climate change debate, there cannot be anthropogenic global climate change in this part of the world and not other on the other side. … If there’s global climate change for everybody, there’s no point closing down the Nanticoke coal-fired power plant on the shore of Lake Eerie and making Ontario rate payers payer double or triple for power, while China and India are free to build 800 coal power plants.”

“ … You can’t ask your own producers to pay twice. Once for their own emissions and than to pay again as they lose market share to countries that don’t pay for their emissions.”

Rubin also mentioned the need for massive investments in public infrastructure, particularly in public transit. For when the 40-50 million North American’s are forced to give up their vehicles over the next decade, they’ll at least have a bus or light-rapid-transit vehicle to get on.

“You know, what folks don’t understand is that during WWII, Detroit stopped making cars and practically overnight transformed itself into a munitions factory making tanks and bombers. Well, if Detroit could transform itself into a munitions factory making tanks and bombers in the 1940s, why can’t Detroit and Oshawa today transform themselves and make buses and light-rapid-transit vehicles instead of SUVs?”

But when asked if that is all he thinks can be done, Rubin made sure to point out how he doesn’t view the government as the saviour or solution. Instead, Rubin said, “I see the market as the solution, frankly. When prices get to these levels [three-digit oil prices], we’re going to start making our own steel again; we’re going to start growing our own food; we’re going to start making our own furniture.

“Because it’s no longer going to make any economic sense for us to source our steel and furniture and food from places like China, because the savings that we might get from their labour costs are going to be more than offset by the fuel costs of getting those products to us.

“So the market is going to bring a lot of those jobs back home. The market is going to being a lot of that production back home. Things will certainly cost more money—everything we will make ourselves, or from our regional neighbours, will costs us more than what it used to cost in the world of cheap oil and cheap wages.

“But I think we’re going to find that tomorrow’s economy is going to look a lot different than today’s economy and not all of the changes will be negative.”

A Brave New World

With all this talk of the end of modern globalization, of a complete reorientation of our shared economy, our discussion then turned to what Rubin envisioned the world of tomorrow would actually look like.

To start, Rubin made clear that “in terms of what we eat, the diets will come more to resemble that of our parents, then what we’re accustomed to [today].” He then related how when he grew up in the 60s, the food he bought was seasonal. “You didn’t see Kiwis, Strawberries, Raspberries and Tangerines in January and February.”

When it comes to vacations, “we’re not going to be able to fly like we used to before. It’s not that there won’t be airlines, but that the cost of flying will probably go back to what it was in the 1960s.” So instead of “Cheng Mei or Machupechu,” Rubin expects most Torontonians to visit places like Algonquin Park or Maskoka.

Then with respect to suburban living: “we’re not going to be able to commute 70-80 kilometres back and forth to work everyday in our SUVs. We’re going to have to either find a way to drive less or work a lot closer to home.”

Because of this change in lifestyle, Rubin notes that “you’re going to find a lot of those far-flung suburbs are going to return, curiously, back into the farmland that they once were, because they collapse in suburban real estate prices and the soaring increases in imported food, now make it all of a sudden economically viable again to raise livestock (here) instead of shipping it from New Zealand. It will make it all of a sudden more important to grow crops, because people aren’t living 50-60 kilometres from the city.”

And as for our cities, “ … where we saw in the last 50 years … urban sprawl, we’re probably going to see increasing urban density, … but with less cars on the road and certainly different kinds of vehicles that we’re used to seeing today.”

Taking all this in, it’s fair to say that assuming a new energy source as abundant and versatile as oil isn’t discovered, the next several decades will represent a difficult transition stage: one from a cheap carbon to a post-carbon age. But it is in those times of crisis, when we turn most to those we love, to those closet to us. It is also in these times when we are most willing to reach out to our neighbour and build the relationships needed to survive. And with the global economy turning local, that is exactly what will happen.

The world we will grow up in will look much different than what our parents were used to, just as the world our parent’s grew up in was far more different than what their parent’s could have imagined. But paradoxically, as outlined earlier, the days of tomorrow may also share many of the qualities most thought were lost from the days of our parents and grandparents.

And as the world finds this new balance, finds a way to adapt itself to this new era, at least we can feel optimistic in the fact that we will be able to share our struggles and our joys together, as we build ourselves a brave new world.

Jeff Rubin (born August 24, 1954) is a Canadian economist and author. He is a former Chief Economist at CIBC World Markets. He graduated from McGill University with a Masters in Economics after completing his Economics B.A. at University of Toronto. He began his career as an economist at the Ontario Government Treasury Department where he was responsible for projecting future interest rates. He moved on to work within the CIBC, becoming its Chief Economist.

In 2000, he correctly predicted that oil prices would be trading at US$50 per barrel by 2005. He then accurately predicted oil would crack the US$100 per barrel mark by the end of 2007.

Rubin’s opinions have been widely reported in the international media. He wrote a widely followed national column in the Globe and Mail, “Ahead of the Curve,” and he has been a fixture on network coverage of the federal budget and other key economic events for almost two decades. He has also made numerous television appearances on ABC, CBC, CBS, CNN and CNBC. His opinions and insights have appeared on the front page of the New York Times, as well as the Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, USA Today, Financial Times, BusinessWeek, Newsweek and the Economist.

ARB Team

ArbitrageMagazine

Business News with BITE

Liked this post? Why not buy the ARB team a beer? Just click an ad or donate below (thank you!)

Share the post "The Age of Energy Scarcity"