Justice Is Served

Citizen-driven initiatives support crime reduction

Written by: Caitlin McLachlan, Staff Writer

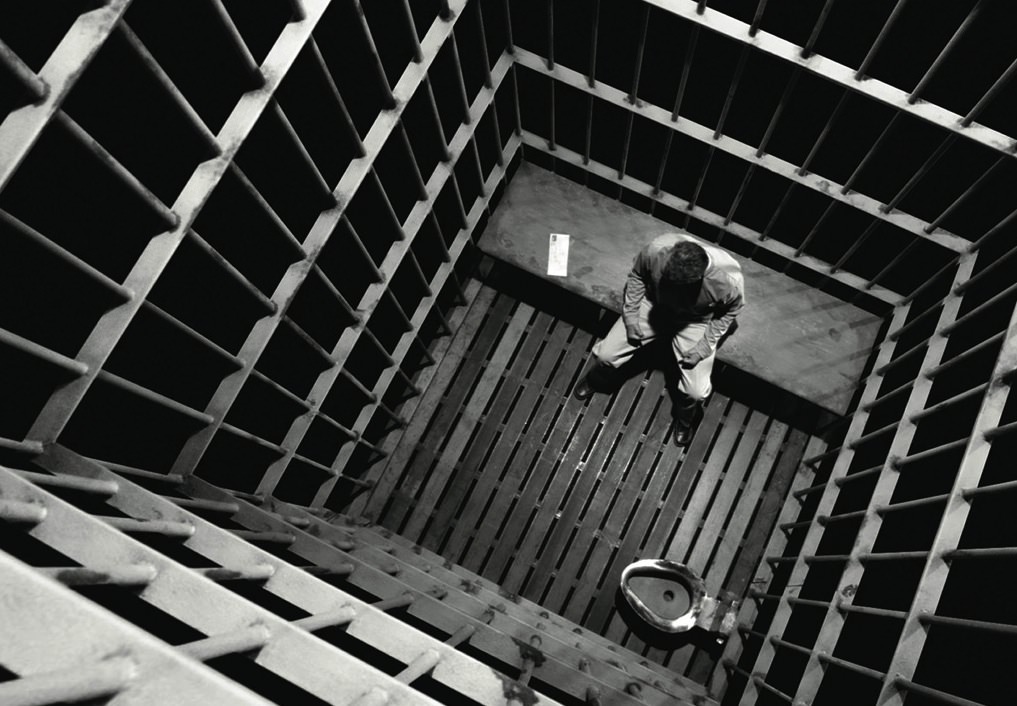

According to the Canadian Council on Social Development (CCSD), it costs between $66,300 and $110,400 to incarcerate one offender for one year in Canada. Taking into consideration the frequency of repeat offenders, does it really make sense to build bigger jails? Fortunately for us, there is another way.

Edmund Burke, a well-known Irish political theorist, once said, “Men are qualified for civil liberty in exact proportion to their own appetites. Society cannot exist unless a controlling power upon will and appetite be placed somewhere, and the less of it there is within, the more there is without.” In other words: you do the crime, you do the time.

Traditionally, crime and punishment have been regarded as two faces on the same coin, and the cost of justice ain’t cheap. According to a study published in Crime Prevention Digest II, as of 1999, achieving a 10% reduction in crime through incarceration costs tax payers seven times more than it would have through social development initiatives.

As advocates for social development, the CCSD highlights it as one of three major avenues to successful crime prevention. The other avenues include situational approaches (improved lighting in public places, self-defense classes, etc.) and police/courts/corrections.

Our House: social development in the private sector

In the spring of 2007, Alberta faced a serious affordable housing crisis. In Edmonton alone, it left more than 200 people homeless. The CCSD reports that residents of poor quality housing are proven to be at risk for behavioural and educational problems, both of which are linked to a higher likelihood of criminal behaviour.

In response to the growing prevalence of homelessness in Edmonton, Dave Martyshuk, CEO of Martyshuk Housing took action. “(The company) is a profit driven corporation. We’ve just happened to make a business out of contributing to the abolishment of homelessness,” says Martyshuk. “It’s never been attempted before anywhere in Canada.”

The business began as an employee housing company in 2004. By 2007, it had become a driving force in Edmonton’s private sector “movement to abolish homelessness.”

“We’re now hosting 208 previously homeless individuals and we will be up to 600 by March,” says Martyshuk. “We just took on another 200 bed complex and a 174 unit apartment building. It’s a lot of people, but we still have 2,400 to go after that.”

The corporation’s vision of a homeless-free community involves a network of private, social, and public sector partners that work together toward this common goal. “(The network) is very large,” says Martyshuk, “it’s kind of like counting the dots.”

Martyshuk Housing works closely with Community Services, addictions experts, home care services, and Edmonton Police Service to provide it’s hard to house residents with safe, healthy, and supportive permanent living arrangements. One partner the corporation works closely with is Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH). It’s a program that provides financial and health related assistance to eligible adults with a disability.

“If you put $1,500 into the hands of someone who is addicted to crack cocaine, he’s not going to pay his rent” says Martyshuk. “AISH and Community Services send us a third party payment on behalf of this individual to ensure that his rent is paid.”

Martyshuk estimates that of the 208 clients the company currently houses, 100 of them are on medication. A common problem in the beginning of the venture was the high level of drug abuse among residents. “We were suffering overdoses among many of our clients,” says Martyshuk. “They’ll buy (medication), sell it, trade it, steal it—whatever they have to do to get their hands on ‘oxys’ and percs, that kind of thing.”

Oxycodone, or oxys, is a narcotic pain reliever used to treat moderate to sever pain. Percocet, or percs, is a combination drug containing acetaminophen and oxycodone. It’s also prescribed to treat moderate to severe pain.

At this point, most people would throw in the towel, but Martyshuk would not be deterred.

“We can use a lot of creativity, and this is one of the benefits of (getting the) private sector involved,” says Martyshuk, “after our last death, we went out, bought a pharmacy and started regulating medications to our clients.”

The pharmacy was so successful that it turned a profit, which the company uses to finance a housing sustainability fund. “Rent is based on $850 month,” says Martyshuk, “if they earn less than $1,100 a month they qualify for a $300 housing subsidy, whether or not they’re on medication.”

Within the first year of owning the MacDonald Lofts, once notorious for violence and drug related activity, EPS responses to the building were reduced by 74 percent. “That represents about a million bucks (of taxpayer dollars),” says Martyshuk, “eight-hundred dollars per hour for EPS response that doesn’t include the ambulances and fire trucks and everything that comes with it.”

In its own way, Martyshuk Housing has put a private sector spin on social development. The corporation has made a significant dent in homelessness; reduced drug related crimes on its premises, and even cut costs by reducing police responses to the area.

“The reason I think we’re so successful is that we can do it on dimes to the dollar,” says Martyshuk. “We take everybody; we expect to have to pick them up, dust them off, and keep them going.”

Angels in the Alley: grass-roots situational crime prevention

Situational crime prevention increases the risk potentials for the offender, minimizes opportunities for crime, and reduces the payoff of completing a criminal act. According to the CCSD, it includes everything from self-defense classes to comprehensive community planning. The Guardian Angels safety patrols fall somewhere in between.

Established in 2007, the Edmonton Guardian Angels is a volunteer citizen group that patrols the city streets as a crime-deterring presence. Dave Schroder is the chapter leader whose initiative led him to contact Curtis Sliwa, founding member of the original Guardian Angels in New York City.

“I just had this feeling that, although I was busy, involved with volunteer work with our real estate board, I just wanted to do something to just try and make a difference someway,” says Schroder.

Patrols typically consist of three to five people. Before going into the streets, crew members frisk each other for weapons (none are allowed), and police are given a cell phone number and the location of their patrol route. “Absolutely no weapons” says Greg Silver, “we try to use our voices more than our bodies. We try to talk people down.” Silver is chapter leader of the Calgary Guardian Angels, he is also owner of Silver Graphic Design.

In fact, although graduated members are trained in self-defense and conflict prevention, the true purpose is to be a presence that dissuades criminal activity and to engage the community.

“The number of confrontations is minimal,” says Silver, “for the most part it’s all about community support.” Schroder agrees, “Most of our patrols might involve talking to locals, just allowing them to express their frustrations about things that are going on, sometimes it’s (about) walking seniors home.”

“We have a professional police force, they are the ones that are really making the difference in the city in terms of effecting crime rates and truly making the city safer,” says Schroder. “Being realistic, we fully realize that the difference we make is really just where we are at that point in time … two hours later, or two days later, I mean really, things are going to take place as they take place.”

Patrols for the most part involve a sort of advocacy for crime reduction. Their presence sends a message to would-be offenders that the community will not stand for it any longer. What separates the Guardian Angels from other citizen organizations is that, according to Schroder, they are willing to “take it one step further.”

“People know who we are, so the drugs and stuff go away, I’m assuming until we leave. We keep our eyes out, if we see somebody thumping on somebody or doing something that’s dangerous, we’ll intervene,” says Silver.

Contrary to the popular notion that intervention leads to vigilantism, the Guardian Angel’s approach is not physically violent. Schroder explains that before anyone even becomes involved, a team member calls the police. The rest of the team ends the scenario as quickly as possible, usually by creating space between the conflicting parties.

Although members of the Guardian Angels have varying day jobs, they are unified by their desire to see a positive change in their community, one that involves citizens taking back their streets one block at a time. “You have two choices in life,” says Silver, “you can sit on your couch and complain about the way things are or you can try to make some sort of a small change.” Schroder agrees, “I would suggest that if people have the capability, there may be a moral obligation to help people that are in trouble.”

The public and the police: a symbiotic intelligence gathering relationship

In 2005, Sgt. Brodeur was tasked with cleaning up drug houses in Edmonton. By aligning with agencies and interested parties, Brodeur cleaned up six houses in one month. Building on this success, he created the Report a Drug House (RADH) program. Within 10 months, the operation had received 186 reports and closed 162 of those complaints.

Interestingly, one of the interested parties associated with Brodeur in the early stages of RADH was Dave Schroder in his capacity as chapter leader of the Edmonton Guardian Angels. Brodeur met with Schroder to discuss the possibility of a collaborative effort. He gave Schroder some business cards to pass out to the people on the street. “It was so refreshing to have somebody who was so open to having a positive impact in the community,” says Schroder.

Although Brodeur has since moved onto other projects, the RADH program continues to run successfully under the leadership of Sgt. Daryl Mahoney. What makes the program so effective is the symbiotic relationship between public participation and police action. “We are a witness driven program. If the community didn’t use us we wouldn’t exist to be able to help them,” says Mahoney.

Mahoney describes RADH as a “crime type specific program targeting drug grow and drug sale operations. We saw a two percent growth in the number of calls from last year to this year with 134 calls to our hotline,” says Mahoney, “we concluded 71 files this year either through warrant, arrest, eviction of the problem, or concluding drug activity had ended.”

There is a resounding opinion among members of the public and private sector that calls for a more integrative and collaborative approach to crime prevention. Recent trends in law enforcement practices are beginning to mirror this sentiment in philosophy and strategic approach.

“There is the traditional enforcement tool for fighting crime but if that is the only tool in your tool box, it really limits your response to any given problem” says Mahoney. “With education, information sharing, resource sharing, retraining/re-education, rehabilitation you have significantly many more tools to use to permanently fix an issue.”

Sgt. Mahoney “wholeheartedly agrees” that there is a need for collaborative initiatives. “Crime reduction is concerning yourself with all aspects of an issue,” says Mahoney, “the individual, neighbourhood, city, global issues, and trends need to be addressed and we all have a part to play and a piece of the puzzle.”

The big picture

It would certainly be simpler to lock offenders up and throw away the key, but this only solves the problem halfway. If we insist on putting up jails rather than addressing the conditions that lead to criminal activity, eventually, we will run out of room to build.

Gradually, communities are evolving away from a segmented structure of isolated parts. The most successful examples of crime reduction involve individual citizens who have discovered a way to reach out across the divide and pull together elements of the private, public, and government sectors. Maybe what Burke really meant was that there is, within each of us, the capacity to impact what affects us.

——————-

Caitlin McLachlan is a freelance writer/photographer whose passions include the environment, culture, serendipitous animal rescue and the mysterious unraveling of a life lived adventurously.

——————-

Sources:

– The Canadian Council on Social Development

– The Edmonton Guardian Angels

– The Alliance of Guardian Angels

– Martyshuk Housing

– Edmonton Police Services, Report a Drug House program

Share the post "Justice Is Served"