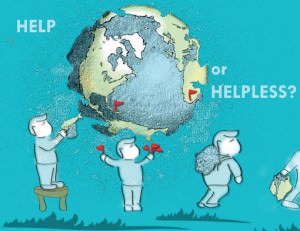

The Pitfalls of Foreign Aid

AIDING (and Abetting?)

It seems almost inevitable that corruption will continue to occur in certain places around the globe. The recent elections in Haiti were a joke, and most African countries are riddled with corrupt officials, most of whom take office because they know it will give them “unfettered access to the treasury,” according to Dr. Dambisa Moyo, an economist and author who believes that aid being sent to Africa is simply not working.

It seems almost inevitable that corruption will continue to occur in certain places around the globe. The recent elections in Haiti were a joke, and most African countries are riddled with corrupt officials, most of whom take office because they know it will give them “unfettered access to the treasury,” according to Dr. Dambisa Moyo, an economist and author who believes that aid being sent to Africa is simply not working.

In her book, Dead Aid, she claims that “six decades of Western aid has itself been an unmitigated political, economic and humanitarian disaster for most parts of the developing world.” Focusing on Africa, she suggests that although there is a “moral imperative” for humanitarian aid, many of the solutions that it offers are mere bandages put over an infectious gash that no one seems to want to address. She suggests that what needs to be done is not to alleviate the surface problems, but to amend the core issues that allow corrupt officials to remain in power.

She criticises government-to-government aid, and aid given by institutions like the World Bank and IMF, for what she considers irresponsible and counterproductive lending. Her argument, essentially, is that the humanitarian aid, for Africa, has taken the form a “debilitating drug” to which the continent has become addicted.

She cites that although the countries received over $1 trillion in aid over the last 60 years, more than half the population still lives in squalor and on less than a dollar a day, per capita income is lower than in the 1970s, over $20 billion annually go towards debt repayment, and all of this at the expense of African education and healthcare.

Of course much of the reason for this is the connection of aid to corruption in Africa. Most government officials have extensive records, including embezzlement, violence, corruption, and many more charges. As such, most of the money and resources sent as aid don’t get to the people, but instead get caught somewhere in the bureaucratic red tape, thusly leaving the country in constant need for more money.

[pullquote]Starvation is a political matter, not an economic matter.[/pullquote]

Mr. Baker concurs with this. He argues that the “more corrupt a government, the more aid is stolen and the more the situation is complicated.” In cases like this, the money is stolen during the procurement and delivery stages, as they are the ones who will make it available to the country. Moreover, once some of the money is finally delivered to contractors and other workers to complete projects such as building roads, hospitals or schools, Mr. Baker says, there is also the danger that they too will “rip off money from what is allocated to them.”

They do this by building under specifications, cutting corners, getting cheaper materials, and a number of other ways that will allow them to keep some of the money. Mr. Baker continued to explain that although not as common, it must not always have to be local contractors; foreign contractors that come to put in work may also partake.

“There was a time,” said Mr. Baker, “when the world bank felt that up to 20% of its allocations ended up as corrupt proceeds….in the combination of corruption and inefficiency.”

Both Mr. Baker and Dr. Moyo agree that a large chunk of responsibility (past and future) lies in the hands of western democracies and western institutions. It is imperative be able to follow recommendations, provide better accountability, and achieve more transparency.

Indeed, in a piece titled Corruption and Foreign Aid, from the Ludwig von Mises Institute, it is claimed that economists Alberto Alesina and Beatrice Weder have found that “there is no evidence that nations and multinational institutions direct their foreign aid to less corrupt governments and away from more corrupt governments.” Jose Tavares, in an essay titled Does Foreign Aid Corrupt? for the New University of Lisbon, claims a 2002 study by Alesina and Dollar used “bilateral trade data to show that the amount of aid is weakly related to the recipient country’s economic performance and strongly related to indicators of cultural and historic proximity between the countries.”

Moreover, Dr. Moyo argues that despite a hearing before the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations in May 2004, where Jeffrey Winters, a professor at Northwestern University, argued that the “World Bank had participated in the corruption of roughly $100 billion of its loan funds intended for development,” the institution has continued to pour money into the country indiscriminately. In yet another instance, “the IMF gave the country the largest loan it had ever given an African nation,” even after one of their appointees to the Central Bank warned them that no creditors would get their money back because of the rampant corruption.

Resonating what Dr. Moyo suggests, the Ludwig von Mises Institute argues, citing Alberto Alesina and Beatrice Weder, that “government-to-government ‘gifts’ actually make government worse over time in terms of both government corruption and economic growth and creates…a ‘voracity effect’ in recipient countries.” Dr. Moyo calls this dependency.

THE POLITICS OF HUNGER

When I asked Mr. Baker, “Why keep doing it?”, thinking that I was referring to sending money, he answered that it was because the people nevertheless do need it. “There are no black and white circumstances in foreign aid,” he said. Sometimes issues have to be muddled through because of the end result. Referring to the relief that the Taliban provided to Pakistanis in the wake of their recent super-flood, since donations weren’t coming from the west, he said, “I don’t object. The immediacy of the need may justify accepting assistance,” even from the Taliban.

But then I clarified my question, and told him that what I was referring to was why keep sending money directly to the government. Why not cut the middle man out? He said because it was impossible. No sovereign would want to give up their right to be the administrator of the country’s finances. As such, his solution was not to stop sending aid, but to build a better, more accountable and transparent global financial system.

As stated before, he believes that the World Bank and the IMF, along with western democracies, must undergo a process of introspection so as to fix our own shortcomings and the avenues on which corruption abroad can piggyback (like, for example, through Offshore Bank Accounts). Speaking of the World Bank and IMF particularly, he believes that their conditions for lending funds or providing foreign aid must be tailored not to the advantage of the western democracies, but to the situation of the recipient country so as to help them become not dependent on aid but self-sufficient.

Dr. Moyo, on the other hand, although also critical of western institutions, including our governments, has proposed a different method to curtail corruption and to therefore make aid actually work. She proposes a sort of capitalist intervention, at least speaking of Africa.

She cites Ghana as an example, “a country where after decades of military rule brought about by a coup, a pro-market government has yielded encouraging developments.” She is referring to the fact that now farmers and fishermen “use mobile phones to communicate with their agents and customers across the country to find out where prices are most competitive … [which] translates into numerous opportunities for self-sustainability and income generation–that, with encouragement, could be easily replicated across the continent.”

She furthermore proposes that Africans enter bond markets, get active in micro-financing and demand revised property laws. And in order to erect a middle class, which every self-sustainable economy needs, she suggests that Africans enter into commercial investment agreements with the Chinese.

While this sounds logical, and even prosperous, one cannot help but wonder if there aren’t other priorities than erecting a business or economic network? Building a sustainable economy that gives opportunities for people to generate their own income is essential, but will mere “encouragement” really help replicate what has happened in Ghana across the world when there are areas of just over one square mile stuffed with one million people? And although competitive pricing may have worked in Ghana, we’ve seen how competitive pricing proved disastrous for Haiti.

Donor nations in the West should not stop sending aid, but should instead formulate stringent conditions, ensuring rigorous accountability and transparency regulations by recipient nations.

Of course that is not to say that the burden is on the beneficiaries’ shoulders alone. The world needs a more transparent system of financial flow. That the West admits mistakes in policies and agreements is a first step; erecting new ones to account for those mistakes is the one that is needed next.

As our conversation neared the end, Mr. Baker vehemently assured me that there is “no need for starvation in the world. There is more than enough food…so starvation is a political matter, not an economic matter. A government is either too corrupt or too incompetent (or both) to prevent people access to food. We don’t need anyone starving.”

ARB Team

Arbitrage Magazine

Business News with BITE.

Liked this post? Why not buy the ARB team a beer? Just click an ad or donate below (thank you!)

Liked this article? Hated it? Comment below and share your opinions with other ARB readers!

Share the post "The Pitfalls of Foreign Aid"